Click

here for Part I via The Wayback Machine

Click

here for Part II via The Wayback Machine

(Be patient - pages take time to load)

Outmaneuvered by Thomas Francis, Radar Magazine, November 10+11, 2005

Part I

Dr. Henry Heimlich's latest

maneuver, a controversial AIDS cure, has many

medical ethicists gagging.

If you have ever found

yourself gasping for air and suddenly been bear-hugged

from behind by a waiter, his fist, placed just below

your sternum, dislodging the food blocking your

trachea with one miraculous thrust, you owe the waiter

a large tip, but you owe your life to Dr. Henry

Heimlich. He's the maneuver man, credited for three

decades as the inventor of the simple,

anyone-can-do-it technique for saving the lives of

dinner companions who have just begun pointing

furiously at their throats while turning blue.

Like most legends Heimlich, a onetime Manhattan society doctor turned medical inventor and gadfly, has his detractors. Many of them are white-coat colleagues openly dismissive of such Heimlich notions as using the maneuver to save people who are drowning and curing AIDS patients by injecting them with malaria.

But none of those naysayers has been as determined to knock Heimlich off his pedestal as the man who first identified himself to me over the phone, in the summer of 2004, as Holly Martins. Dr. Heimlich, he told me impatiently, is a scam artist, promoting crackpot theories and stealing credit for other doctors' inventions. The word Martins used to describe Heimlich's career was fraud, and he said he had the evidence to prove it.

Holly Martins is not his real name; it comes from the Joseph Cotten character in the noir classic The Third Man. It is odd to use a fake name to expose a fraud, as Martins would concede in later conversations. But he was convinced it was the only way to elicit the truth from all the colleagues Henry Heimlich had burned over the years. For surely they would have left out the most sordid details had Martins used his real name, which is Peter Heimlich.

"You tell me how I'm supposed to call a doctor and say, 'Hi, I'm the son of Henry Heimlich, the scourge of your life. Would you tell me the truth about him?'"

He then went on to reveal who really invented the Heimlich maneuver. And it wasn't long before my own investigation of Dr. Henry Heimlich uncovered ongoing unsupervised experiments with AIDS patients in Africa and China that Peter Lurie, one of the country's leading medical ethicists, says are absolutely outrageous and could be the difference between life and death." Dr. Heimlich's methodology proved so difficult to verify, let alone justify, that his own research director at the Heimlich Institute in Cincinnati warned him about criticism from the medical establishment and called for better cooperation with local medical review boards. Heimlich's Trumpian response: "You're fired!"

Peter Heimlich and his wife Karen Shulman live in a high-ceilinged French provincial house outside New Orleans where the sun pours in like syrup on a sultry midsummer day. On the July morning when I first visit them, more than a month before the devastation that would be wrought by hurricane Katrina, they have thrown open the doors to catch a Louisiana breeze in lieu of air conditioning, tropical storm Cindy having knocked out the power the night before. Peter, a lean and whiplike six-foot-four, is padding around barefoot, made restless by the sudden lack of telephone or internet access to the world. Karen is the more cautious, analytical half of the couple, not as emotionally attached to the mission as Peter but every bit as fascinated. They've spent the last four years obsessed with taking down Peter's father.

For the first 48 years of his life Peter distanced himself from his father's career and celebrity. A year or two might slip by between calls from his parents. But in 2001, Peter says, he learned of serious health problems in his family. He refuses to say what those problems were, but he insists he was appalled to learn that his father was refusing to address them.

"My father's the great Dr. Lifesaver," Peter says bitterly. "How could he have let this happen?" When he tried to get the facts, he says, his father hung up on him and his mother wouldn't respond to his letters.

Peter and Karen began to wonder whether there were other family secrets worth looking into as well. At first glance Peter Heimlich is not an obvious choice for sleuthing around in medical archives; his life has included stints as a musician and as a successful businessman. But there may well be no one better prepared to solve the mystery of his father. "I speak Heimlich," he says. "To understand Henry you have to see behind a kind of curtain, because his methods are unconventional and his goals seem to be..." He searches for the right word. "Irrational. I don't think the medical field had ever seen anyone quite like him. The Henry Heimlich story is so improbable and confusing and puzzling and challenging. It's like a Zen puzzle."

A small corner study across the hall from Peter and Karen's bedroom is the nerve center of their campaign. From their computer they control the website heimlichinstitute.com, which was deliberately named so as to compete for web traffic with Dr. Heimlich's site, heimlichinstitute.org. (Dr. Heimlich's lawyers recently succeeded in forcing Peter to change the website's name. He went with medfraud.info.") The site has revealed many Heimlich secrets to anyone with internet access. Peter works the phone while Karen stands nearby, jotting notes to remind him to broach an important subject with whoever is on the line.

Peter had never known his father to have an unconventional mind, to be a tinkerer who followed creative impulses, so when the term Heimlich maneuver first entered the lexicon in the late 1970s Peter was astonished. He was living in California, writing songs and playing in rock clubs, hoping for a break. From time to time Henry would mail him an envelope thick with articles touting the Heimlich name and this new invention. Peter tossed the stories, unread, into a file folder.

Eventually he scrapped his musical ambitions and turned to less stimulating but more lucrative work, headhunting in Silicon Valley, then starting up a fabric import business with Karen. Peter says that his efforts to reach out to family members were rejected (and that he has the letters to prove it). So when his parents stopped responding to his questions, he began looking elsewhere for answers. The first place he turned was the file of articles that Henry had mailed him over the years. The more Peter read, the murkier it all became. In one article Henry tells an interviewer that Peter had submitted scripts for The Twilight Zone, which was false. "It was like, 'Oh my God, he just made it up!'"

Strangest of all was the frequent appearance of a vaguely familiar name: Dr. Edward Patrick. Peter had remembered Patrick visiting the family home in Cincinnati in the early '70s, but Patrick had always been introduced as an electrical engineering professor, not as an M.D., much less as Henry's research colleague. At home Henry had often spoken of his many career ventures, and his failure to mention Patrick was, to Peter's thinking, conspicuous by its absence." So how to explain Patrick's presence in all those articles?

"For us, it was like the beginning of Blue Velvet, when the guy finds the ear and it leads him down this rabbit hole into a nightmare world," says Peter. He and Karen befriended librarians and hospital records clerks, mastered the PubMed medical database, and learned how to navigate public records law. "Karen's joke," says Peter, "is that I got to know my father through the Freedom of Information Act."

I was working at an alternative newsweekly in Cleveland when Holly Martins first contacted me. That conversation led me to call Dr. Patrick to get his account of the invention of the Heimlich maneuver. Patrick explained in painstaking detail how he, as an electrical engineer, had first applied engineering concepts to the problem of choking. He had a harder time describing what Henry Heimlich had contributed, but Patrick compared their partnership to that of the Wright brothers.

Whoever had the original idea, Heimlich, who declined all requests to be interviewed for this article, deserves credit for his marketing skills. He had a way with the media; in the late '70s and early '80s he attracted widespread coverage of the Heimlich maneuver, while accusing the Red Cross of risking lives by refusing to recommend it over the application of back blows, which was then the standard intervention for choking victims. His point was neatly driven home by slogans such as back blows are death blows."

"He was able to tailor his message to what reporters wanted to hear," says Peter. "The image of the underdog, the maverick, the David vs. Goliath of medical bureaucracy, was a compelling story."

At the same time Heimlich was gearing up for a showdown at the 1985 American Heart Association conference, at which a panel of experts in each safety field would decide whether new evidence warranted new recommendations for approved actions in emergencies. The chairman of that conference, Dr. Bill Montgomery, knew that Heimlich was prepared to do battle with the committee on the topic of choking.

"It was this huge publicity campaign. He was something to be reckoned with, Montgomery recalls. "He threatened to sue us all and write to the presidents of our universities. It was brazen, terrible, unusual."

Different studies reached different conclusions about the most effective method for choking intervention: the Heimlich maneuver, back blows, or chest thrusts, which consist of pushing down on the victim's sternum, as with CPR. There was a dearth of data. As one panel member, Dr. James Atkins, summarizes the situation, the committee could "adopt something that has no evidence, something that has very poor evidence, or something that has mediocre evidence."

Heimlich's evidence might have been even less persuasive, however, had he informed the panelists that his own foundation had financed the one study demonstrating the superiority of the Heimlich maneuver. In fact, they didn't learn this until 20 years later when I told them.

Heimlich's rivals folded. Dr. Archer Gordon, the advocate of back blows, was too scared even to show up at the conference. Dr. Charles Guildner, the champion of the chest thrust theory, didn't back down so easily, leading Heimlich to make good on his threats: Heimlich accused Guildner of unethical medical practices and petitioned to have his license stripped. Says Guildner, "He tried to bury me. The panel ruled for the Heimlich maneuver.

Ed Patrick, meanwhile, stood by Heimlich throughout the whole contretemps, defending the maneuver against all comers. So it must have been a painful shock when, on a September day in 1985, a reporter told Patrick that Heimlich was claiming sole credit for having invented it. Patrick, who staged his own celebratory press conference to coincide with Heimlich's, had been left at the altar. But for reasons that would become clear only much later, Patrick never retaliated.

"I would like to get proper credit for what I've done," Patrick told me. "But I'm not hyper about it."

Patrick's ex-wife Joy tells a different story: "Whenever my kids would say 'Heimlich maneuver,' he would correct them and say, 'Patrick maneuver.'"

Peter believes Patrick had good reason for not challenging Henry's sole claim to the maneuver. "I turned up some of Ed's medical license applications and other documents," Peter explains. "And they contained fake dates of birth and dubious job titles and credentials. Ed even claimed that he did three years of residencies at Jewish Hospital, all supervised by Henry." But the chief resident at Jewish Hospital at the time says Patrick was not a working resident there.

At the time, Heimlich's career as a surgeon was drawing to an ignominious close. There had been at least one incident when he passed out at the operating table, leaving another surgeon to finish the job. Heimlich was having trouble obtaining malpractice insurance, Peter claims, and his personality hadn't endeared him to the rest of the Jewish Hospital staff. In 1976 he left the hospital.

"I think the maneuver was a life raft for him," says Peter. "It was his last chance, and he knew it. It wasn't only his need for fame, his ego needs. He was at a dead end in his career, and the maneuver came along and offered him a way out. That's why he worked so hard, so relentlessly to promote it. It's why he took so many risks."

Henry Heimlich, now an alert, active 85-year-old, might have counted himself among the most fortunate of his generation. The Great Depression barely intruded upon his comfortable boyhood in the New York suburb of New Rochelle. Cele Rosenthal, Heimlich's sister, remembers how effortlessly he sailed into medicine, how he seemed marked for great accomplishment. "One doctor told my mother that someone with a gift such as he had came along once every 100 years, says Rosenthal. "He was always, always praised."

Henry served for a time in Mongolia during World War II before resuming his medical training. Returning to New York in 1945, he settled into a small practice on Fifth Avenue; his patients came from Manhattan's social elite. His circle included Arthur Murray and his wife Kathryn, who were at the height of their fame, with a chain of social dancing studios and their own TV show. In 1951 Henry married their daughter Jane.

The Murrays bought the newlyweds a sprawling house in the leafy Westchester suburb of Rye, and then bought the house next door for themselves. Peter remembers his grandfather's dismissive, mocking attitude toward his father, but he believes Henry learned about promotion from Arthur Murray. "He wasn't just selling dance lessons," says Peter of his grandfather. "He was selling the hope that learning to dance would make you popular and would introduce lonely people to a mate."

The Heimlichs moved to Cincinnati in 1969, when Henry got the appointment at Jewish Hospital. Peter, by now a teenager, cultivated his interests in music and movies. While his parents were going to the opera, he was singing in Cincinnati's first punk band. Peter also began to bristle at his mother's starchiness and his father's egocentric mealtime monologues. He remembers interrupting one of Henry's self-aggrandizing tales to say, "Hey, you put on your pants one leg at a time like everybody else." By Heimlich family standards, it was an incendiary comment, and Henry flew into a rage.

Dr. Heimlich's first claim to medical fame was a surgical technique that involved replacing a patient's damaged esophagus with a gastric tube. In 1955 Heimlich had published a paper in the journal Surgery describing how he had performed the operation on dogs. A Romanian physician, Dr. Dan Gavriliu, wrote to Surgery to point out that he'd been performing the same operation successfully on humans for four years.

Karen discovered a 1957 article in Surgery written by Heimlich in which he conceded that Gavriliu was indeed first to perform the operation on humans. It might have been chalked up to coincidence - two inventors arriving at an idea within a few years of each other - except that Heimlich still takes credit for the "Heimlich Operation" on his website. His listing in Who's Who in America reads, in part, "Achievements include the development of the Heimlich Operation (reversed gastric tube esophagoplasty) for replacement of esophagus."

Peter leaked the story to the Cincinnati Enquirer, whose front page expose in March 2003 quoted Gavriliu as calling Heimlich a "thief." In the article Heimlich admitted again that Gavriliu had been the first to perform the procedure and insisted he had given Gavriliu credit, which he had, though selectively and in most cases well out of the public eye.

Next, Peter and Karen took aim at a lesser-known invention, the "Heimlich chest drain valve," which was used on the battlefield in Vietnam to save soldiers from dying of a collapsed lung caused by a chest wound. According to Heimlich's press statements the invention saved tens of thousands of lives, including among the North Vietnamese, after the American Friends Service Committee shipped valves to both sides in the war. Henry often tells the story of a trip to Vietnam during which he received a hero's welcome because of his valve.

But the Quakers have no record of distributing the valve. Peter contacted the American Friends Service Committee, the Quaker group that provides aid in foreign conflicts. "They checked deep in the archives and contacted several staffers from the '60s," says Peter. "No one had even heard of the Heimlich valve." AFSC spokeswoman Janis Shields says that if the valves had been shipped to North Vietnam, there would have been documents. The AFSC's shipments to North Vietnam consisted primarily of penicillin.

Part

II

Over the objections of

medical ethicists, Dr. Henry Heimlich continues to

push "malariotherapy" as a treatment for AIDS.

By the late 1980s Henry Heimlich's anti-choking maneuver was world famous, and he was publicly musing over the question, what next? His first priority was establishing the Heimlich maneuver's use in drowning rescue, in lieu of CPR. Second, he vowed he could cure AIDS by treating HIV-positive patients with malaria. He even considered running for president in order to bring world peace.

The maneuver-for-drowning campaign was based on the premise that water must be forced out of the lungs. "You can't blow air into water-filled lungs," according to Heimlich's slogan.

There's just one problem with that thesis. "The idea that inhaled water fills up the lungs in drowning is totally incorrect," says Rear Admiral Alan Steinman, who crafted the U.S. Coast Guard's guidelines for cases of near-drowning. Steinman and three other drowning experts I consulted all said that an involuntary response, laryngospasm, seals the lungs at the moment fluid threatens to flow in. Only a very small amount of water ultimately gets into the lungs after the spasm relaxes.

Employing the Heimlich maneuver may be not only ineffective but lethal, according to Dr. James Orlowski, another drowning expert. In 1987 Orlowski published a paper describing a 10-year-old drowning victim who had suffered complications from the rescuer's use of the Heimlich maneuver rather than CPR. A boy who might have been saved slipped into a coma and later died.

Heimlich cites his own list of cases supporting his maneuver's efficacy against drowning, but the people reporting these cases have prior associations with Heimlich himself. Former Washington, DC, fire surgeon Victor Esch, for example, claimed to have saved a man from drowning at Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, in August 1974 by using the Heimlich maneuver. Esch, who told me he has known Henry Heimlich for decades, can offer no hospital reports or witnesses. And he has told several different versions of the same story. During the course of one interview he told me that the incident happened at Rehoboth Beach, only to deny it five minutes later and insist that it happened at another beach.

Despite his lack of independent evidence, Heimlich had credibility with the public and the media. He could point out that at one time the choking experts had been skeptical of his maneuver, and since that turned out well they ought to trust his insight on drowning, too.

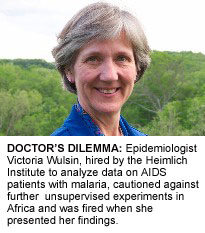

By the same tortured logic Heimlich wants to convince the world of the therapeutic power of malaria. His hopes for using the illness to cure cancer and Lyme disease had already been scuttled in the early 1990s, after the Mexican authorities shut down a clinical trial in Mexico City, according to Heimlich's friend Harry Gibbons. So Heimlich - who trained as a thoracic surgeon and has no background in immunology - gambled that "malariotherapy" would solve the AIDS puzzle. To some researchers, including Dr. Victoria Wells Wulsin, the theory held some intuitive appeal.

"I was curious about malariotherapy, because infection can be an immune booster," says Wulsin, an epidemiologist hired by Heimlich in August 2004 to study the theory's plausibility. "You get sick, and your body responds with white blood cells. That's what you need to fight off HIV, right?"

But more than 10 years earlier the Centers for Disease Control had declared that "No evidence currently exists to indicate that malaria infection would beneficially affect the course of HIV infection." And since malaria might be harmful to a patient whose immune system is already compromised by HIV, the agency added that clinical trials "cannot be justified." The CDC warning had come in direct response to Heimlich's first malariotherapy experiments in China - work that, like the subsequent trials in Africa, is shrouded in mystery and which continues to raise serious questions about its efficacy and the apparent disregard of basic ethical standards in medical study.

Last January Dr. James Kublin, who analyzed the connection between malaria and AIDS in the East African nation of Malawi, published his findings in the respected British medical journal Lancet. Kublin reported that malaria infection can actually exacerbate the speed of HIV's attack on the body.

"Malaria causes immune activation, and immune activation is associated with, of course, an increase in the number of immune cells," says Kublin. "But that's a transient increase in CD4 cells. The problem with that is when you increase the number of CD4 cells you also increase the number of potential targets for HIV. And those CD4 cells are then infected by the virus - and then turn out more virus."

"Using malaria as a 'therapy' is really malpractice and probably should be criminal." says Mark Harrington, who analyzes AIDS research.

"It is clearly deleterious to people with HIV to get malaria. It can accelerate their mortality," says Mark Harrington, executive director of Treatment Action Group, which analyzes AIDS research. "Using malaria as a 'therapy' is really malpractice and probably should be criminal."

Heimlich's first clinical trial took place at Yishou Hospital in Guangzhou, China, in 1993. In advance of this experiment, Heimlich circulated a study protocol that called for two groups of HIV-positive volunteers to be infected with malaria, which would then be allowed to go untreated for either two weeks or four weeks. It stipulated that the volunteers should be treated for malaria only if their temperatures topped 106 degrees.

For AIDS experts the study's most galling aspect - recorded in the final published report - was its rule that the HIV-positive volunteers express a "willingness to not participate in other HIV therapies for [the] duration of the treatment and follow-up period." This meant the volunteers would go as long as two years without treatment. Somehow Heimlich and his colleagues found eight HIV-positive patients to enroll in the study.

Xiao Ping Chen, the Chinese researcher who oversaw the study on Heimlich's behalf, claims that the patients all survived and "remain clinically well" as of the follow-up period's close. But the study does not cite data for six of the eight patients' past six months, nor does Chen explain the omission. Heimlich refused to provide me with Chen's contact information, nor did Chen respond to questions sent to e-mail addresses cited in his published material.

For the second study Heimlich enlisted the assistance of John Fahey, a UCLA immunologist, putting him in touch with Chen, with whom Fahey oversaw a clinical trial that tested malariotherapy on 12 HIV-positive Chinese patients beginning in 1998. Again, the study took place in Guangzhou. Again the subjects were injected with malaria, and the disease was allowed to go untreated, this time for a minimum of 10 malarial fevers, i.e., two to four weeks. The patients were placed in three groups according to their CD4 cell counts per cubic millimeter of blood. At one end were those for whom HIV had had only a modest impact on their immune systems, with CD4 counts of over 500. At the other were patients whose CD4 counts had fallen below 200, meaning they had developed full-blown AIDS and would die without a proven intervention such as antiretroviral therapy.

As would be expected, the malaria produced the "transient" burst of immune substance predicted by AIDS experts, but as they might have also predicted, the elevated immune levels didn't last long. The resulting paper, published in the Chinese Medical Journal, shows that most of the patients displayed CD4 counts that were too scattered to draw a conclusion. One patient - the one with the most advanced case of AIDS - died. The data for the patient who began with the second-lowest CD4 count simply disappears at the end of the study. Chen cites a telephone interview with the patient in which he confirmed the patient's being "clinically well."

But that seems unlikely, given the rule that the patients were prohibited from getting antiretroviral therapy, not to mention the possibility that malaria infection hastened the patients' progression to AIDS. And what happened to the six HIV-positive people whose data vanished six months after the first study began?

"That's my question," says Kublin, author of the Lancet study. "Did all of these people survive those two years? I mean, there are two subjects with CD4s less than 200, and [the researchers] don't have any data on them. I suspect they died."

More recently Heimlich has sought to bring malariotherapy to another location where Western medical ethical standards are loosely observed: Africa, where AIDS kills 2 million people each year. Neither Heimlich nor his spokesman Bob Kraft would answer my request for information about Heimlich's studies in Africa. But a number of ancillary characters who have assisted Heimlich's efforts are less guarded, and through them a picture emerges, incomplete but still ghoulish.

While researching her report Dr. Wulsin, who has field experience with AIDS in Africa, says that Heimlich's assistant, Dr. Eric Spletzer, gave her data that had been gathered from Africa - CD4 counts, apparently from HIV-positive patients who also had malaria - but would not disclose the usual contextual information. There was no signature from the researcher who took the data, and no explanation of how it was gathered. This struck Wulsin as strange; she needed that information to make sure the data wasn't biased. When she asked Spletzer for it, he refused. "I think Eric and Hank [Heimlich] knew things that, for a variety of reasons, they didn't want to share with me," says Wulsin, who declines to say more about what those reasons might be.

Wulsin's report, based on information gathered from inside the Heimlich Institute, offers the best glimpse into the size and scope of Heimlich's malaria endeavors. It refers obliquely to "an American sponsor" (Wulsin says she was never told the sponsor's identity) who in 2000 collaborated with the Heimlich Institute in conducting a malariotherapy study in East Africa. In 2003, says the report, this unnamed sponsor "commenc[ed] infection with malaria among 12-13 HIV-positive East African patients."

A footnote says that this study "lost" four or five subjects during the follow-up period, which would reduce the number of patients in the study to eight.

"There was a firewall," Wulsin says of the problems she faced in getting information from the institute. "I could see from Heimlich's point of view why they wanted to protect their sources, but it was certainly a disagreement that we had. I'm pretty Western, and I said, 'No, I'm not going to place any stock in these results.'"

Mekbib Wondewossen is an Ethiopian immigrant who makes his living renting out cars in the San Francisco area, but in his spare time he works for Dr. Heimlich, doing everything from "recruiting the patients to working with the doctors here and there and everywhere," Wondewossen says. The two countries he names are Ethiopia and the small equatorial nation of Gabon, on Africa's west coast.

"The Heimlich Institute is part of the work there - the main people, actually, in the research," Wondewossen says. "They're the ones who consult with us on everything. They tell us what to do."

Wondewossen says that the project does not involve syringes full of malaria parasites. "We never induce the malaria," he says. "We go to an epidemic area where there is a lot of malaria, and then we look for patients that have HIV too. We find commercial sex workers or people who play around in that area." Such people are high-risk for HIV, and numerous studies show the virus makes its victims more vulnerable to malaria.

A key to containing malaria is speedy treatment. In the most resource-poor areas, clinicians who lack the equipment necessary for diagnosing malaria will engage in presumptive treatment at the first signs of fever. This, says Wondewossen, runs contrary to Heimlich's interests. What physicians in Africa usually do "is terminate the malaria quickly when someone gets sick," he says. "But now we ask them to prolong it, and when we ask them to do that, the difference is very, very big."

Untreated malaria is horrible and includes periods of 105-degree fever, excessive sweating followed by chills and uncontrollable shivering, blinding headaches, vomiting, body aches, anemia, and even dementia. Heimlich's malariotherapy literature recommends the patient go two to four weeks without treatment. Delay in treatment, warns the CDC, is a leading cause of death.

Wondewossen says that the researchers involved in the study are not doctors. He refuses to name members of the research team, because he says it would get them into trouble with the local authorities. "The government over there is a bad government," he says. "They can make you disappear."

Wondewossen won't reveal the source of funding for this malariotherapy research. "There are private funders," he says. But as to their identity?"I can't tell you that, because that's the deal we make with them, you know?" He scoffs at the question of whether his team got approval to conduct this research from a local ethics review board. Bribery on that scale, he says, is much too expensive: "If you want the government to get involved there, you have to give them a few million - and then they don't care what you do."

Heimlich claims to believe in the importance of evaluating patients through every stage of malariotherapy, but without being present for the onset of malaria his researchers would have a difficult time tracking the disease's effect on the patient's viral load. That doesn't deter him from looking to the future. Wulsin's report contains a forecast for a clinical trial in Africa that would begin by enrolling 75 patients in 2007, then another 20 to 30 in 2008. These projections are based, however, on the premise that current trials will bear out Heimlich's theory.

In particular Heimlich targeted South African gold mines, which employ a large population of poor, AIDS-ravaged miners who live in prison camp-like conditions. Wulsin told me that over the last several years Heimlich has sought to convince South African gold mining companies of the merits of malariotherapy, in the hope that they would allow him to conduct clinical trials on the miners, many of whom are HIV-positive. Wulsin was to have a role in this effort. She says that in 2002 the gold mines sent doctors to visit Heimlich in Cincinnati to discuss the prospects for a study, but the talks eventually broke down over disagreements over who would pay for what. According to Wulsin, Michele Ashby - then the chief executive of Denver Gold Group, an international consortium of gold mines - was acting as a broker between Heimlich and the mines. Wulsin's report notes that Heimlich spoke at the Mining Investment Forum in 2002, in Denver, where Ashby introduced him to "12 CEOs who operate in South Africa and other locations." When I called to ask Ashby about her role in malariotherapy, she hung up on me.

I think the idea was that here is what you call a captive audience," explains Wulsin. "You don't have to hospitalize them." This eliminated one of the most prohibitive costs, and though Wulsin doesn't mention it, the subjects' remote location made interference from regulators less likely.

Wulsin had been lured to the Heimlich Institute with the understanding that she'd be groomed to take over its presidency from Heimlich himself. After a few months, however, she began to suspect that this honor had a string attached: She had to produce a document supporting further malariotherapy trials. Instead her report proposes significant upgrades in safeguards, oversight, and accountability before moving forward. Wulsin even suggests changing the name "malariotherapy" to "immunotherapy," suggesting that the very treatment itself was tainted.

In December 2004, the day after issuing a draft of her report (which has been obtained by Radar), Wulsin was fired.

I requested an interview with Heimlich through his spokesman Robert Kraft, but I was turned away, ostensibly because the issues I wanted to discuss were similar to those raised by Peter Heimlich and posted on his website.

This April, Henry Heimlich came to Chicago, where I now live, to give a speech before a local organization called the Save a Life Foundation. I caught him in the hall afterward. When I told him I was a reporter, his face lit up. I guided him to a table, but before I could ask him to sit he asked my name.

I told him, and he recoiled. The urbane manner of a moment earlier vanished. He became petulant, scowling. My first question, the softest of the group, didn't bring a direct answer. "You're fishing around with nonsense," he said, obviously aware that I was reporting some of his son's charges.

I reminded him that in the past he'd said he welcomed criticism. He was drifting away, so it was my last chance to engage him. I dropped the name he dreaded most: Peter.

Heimlich's face went ashen, and he mumbled something I couldn't make out. Then he turned toward to the conference room. Before opening the door, he turned back. "You should be ashamed of yourself," he said.

Later I would e-mail a list of questions to Kraft, who responded that Heimlich would not be giving answers.

Janet Heimlich, Henry's daughter and Peter's sister, grudgingly agreed to an interview. She said Peter had "cut himself off from the family." Though she hasn't personally looked into the subjects, she wasn't troubled by malariotherapy. "It's controversial, and he has critics," she said, "but he has had critics his whole career. That's just par for the course. He had critics when he came out with the Heimlich maneuver for choking."

She added that she had talked to "a lot of people who have strongly supported my father's work, including malariotherapy."

But when I asked her for the names of qualified experts who could endorse Heimlich's positions, she declined. "I have not spent time researching this the way my brother has," she said. "He has handed you - as well as many other journalists who have bitten - on a silver platter all these sources who have a huge ax to grind with my dad."

In pure marketing terms, the vaunted Heimlich brand is losing value. Bill Montgomery, the official who chaired the 1985 conference in which the Heimlich maneuver was ruled to be the best choking rescue, notes that by 2000 the AHA national guidelines recognized chest thrusts and back slapping as appropriate alternatives to be used in sequence with the Heimlich maneuver. Chest thrusts create more force than the maneuver, according to recent studies, and may well become the preferred response in the future.

Peter Heimlich knows that by exposing his father he invites speculation - and criticism - about his motives. He and his wife Karen are bracing themselves for it.

"We're both private people by nature," says Peter. "We're not grandstanders. We're a couple of fabric business owners, and we uncovered this big rat's nest. We never made any threats. We never attacked anybody." Still, he knows that armchair psychoanalysts will have a field day with him. Peter says such speculation misses the point.

"Do I wish I had a more loving father?" he asks. "I've seen friends who have loving fathers, and it seemed really strange to me. I'd say, 'Gee that would be nice.' Am I bitter? Not at all. We all get the hand we're dealt. I think I was much worse before I found out this stuff. At least I know what's real now."

In the beginning he was angry with his parents, but as the scope of his father's deception became apparent, it became a battle of wills: Henry's efforts to extend the Heimlich legacy versus Peter's efforts to destroy it.

"The last thing I wanted," says Peter, "was to make this my life's work. It only became my life's work because I had no choice, because if I had let go I would have had to live with the consequences."

I ask Peter if he hates his father.

"He's a stranger!" Peter exclaims. "Do I love him or do I hate him? I don't even know who this guy is. Do I hate what he's done? Yes. That's easy, because it's crazy, it's destructive."

To hear Peter tell it, there's nothing complicated in his Inspector Javert-style pursuit of his own father.

"Who wouldn't want to know why somebody is keeping a secret?" he asks. "That's part of the appeal. Why didn't they want me to know this? And the only answer is they knew that if I found out I'd blow the whistle.

"Which is exactly what I did," he says, allowing himself a triumphant grin.

Photos:

The Heimlich Institute, Peter Heimlich, Arthur

Murray and New York Daily News